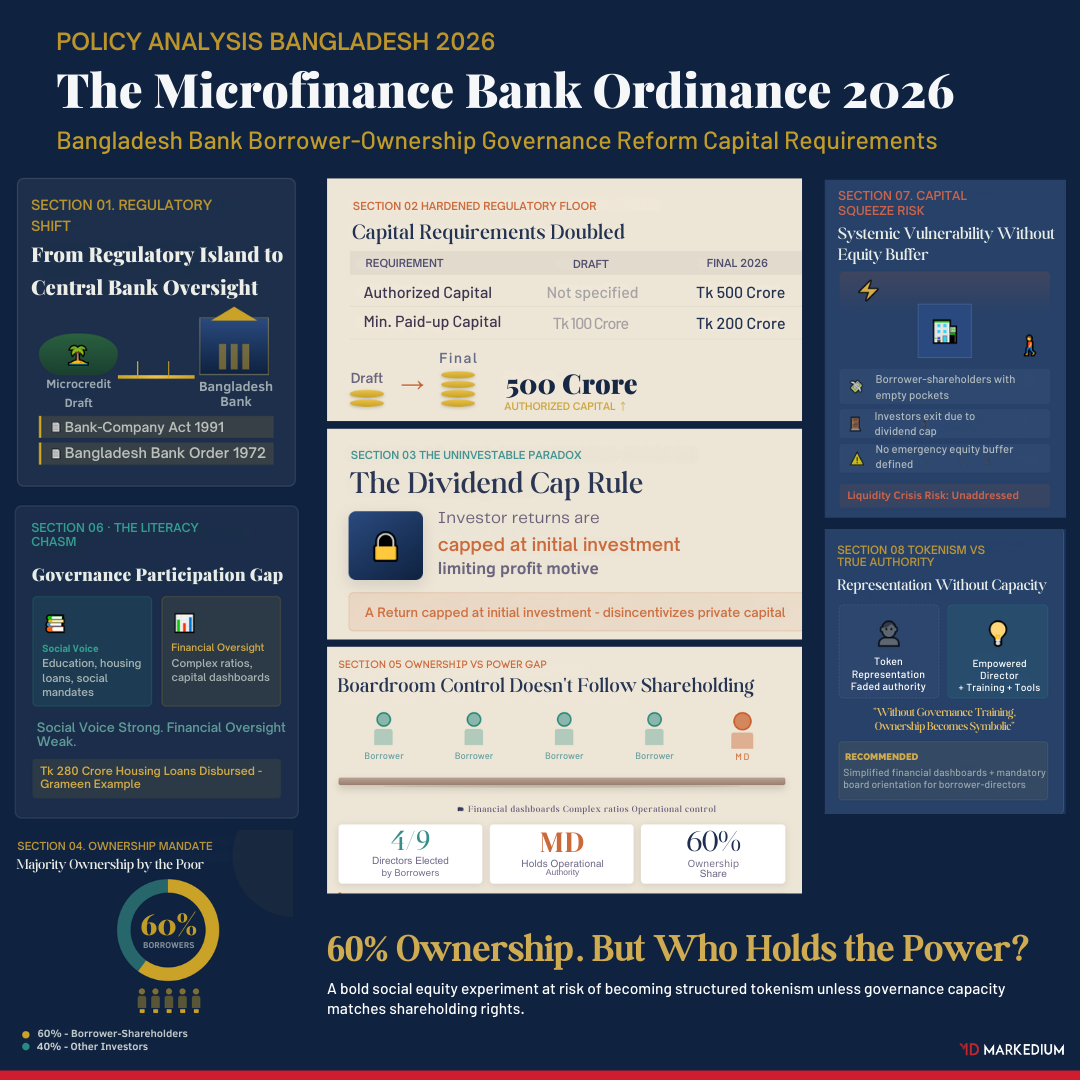

Bangladesh’s Microfinance Bank Ordinance of 2026 marks a decisive departure from earlier experimental drafts, firmly integrating microfinance institutions into the mainstream banking system under the oversight of Bangladesh Bank, the Bank-Company Act of 1991, and the Bangladesh Bank Order of 1972. This transition effectively ends microfinance’s era as a light-touch, parallel regulatory domain.

The ordinance raises the financial entry bar substantially, setting authorised capital at Tk 500 crore and minimum paid-up capital at Tk 200 crore, double the figures proposed in the original draft. These requirements signal that the state envisions robust, institutionally serious entities rather than experimental credit cooperatives.

The ordinance’s most consequential and controversial provision concerns profit. General investors are legally capped at recovering only their initial investment, while borrower-shareholders face no such limitation. Mandating that borrower-shareholders hold at least 60 percent of capital, the law explicitly prioritises poor ownership over private capital accumulation. The social rationale is clear, but the economic consequence is an “uninvestable paradox”: no rational investor will commit risk capital to a Tk 200-crore venture where upside returns are legally prohibited, effectively closing these institutions off from traditional private capital markets.

The Grameen Bank precedent illuminates what borrower ownership can achieve and where it falters. Borrower-leaders shaped Grameen’s foundational “Sixteen Decisions” through genuine grassroots dialogue in the early 1980s, influencing social policy on dowry, education, and housing. By 2022, housing loan disbursements had reached Tk 280 crore for rural homes. Yet researchers consistently identify a “literacy chasm”: borrower-directors, often lacking formal education, tend to shape an institution’s social character while professional staff retain effective control over financial operations.

The 2026 Ordinance risks entrenching this disparity. Although borrower-shareholders elect four of nine directors, the ordinance is silent on mandatory financial literacy requirements. Without structured governance training, 60 percent ownership may function as legal symbolism rather than genuine authority, leaving managing directors and institutional nominees to dominate decisions on capital adequacy and liquidity management.

Unless supplementary regulations address this gap directly, Bangladesh’s microfinance banks risk becoming elaborate exercises in tokenistic governance rather than genuine instruments of financial empowerment.

For more updates, follow Markedium.

Leave a comment